The Misguided Diet

& The Need for Physicians to Enter the Conversation

“People are fed by the food industry, which pays no attention to health, and are treated by the health industry, which pays no attention to food,” once said American novelist, Wendell Berry, perhaps best encapsulating the current state of our inherent dietary disconnect. At a time when nearly 70% of the U.S. population has at least one diet-related chronic illness – whether cardiovascular disease, an autoimmune disease, diabetes, cancer, or otherwise – we are at peak confusion in terms of dietary messaging.

Author of several New York Times best sellers, Michael Pollan, observed, “It does seem to me a symptom of our present confusion about food that people would feel the need to consult a journalist, or for that matter a nutritionist or doctor or government food pyramid, on so basic a question about the conduct of our everyday lives as humans.”[i] Pollan wondered, “What other animal needs professional help in deciding what it should eat?”

A century ago, the top killers were infectious diseases. Now, the killers are primarily lifestyle diseases, such as heart disease and cancer. Heart disease, the number one cause of death in the U.S., is both preventable and reversible by removing the problem: poor diet.

According to Dr. Robert Lustig, “The cellular pathways that lead to chronic disease are not druggable, but they are foodable.”[ii] It’s based upon the same rationale that Dr. Neal Barnard, President of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, once argued, “Rather than viewing pharmacological interventions as ‘conventional’ and nutritional interventions as ‘alternative,’ these views should be reversed: medications for these conditions should be considered ‘alternative’ treatments when nutritional improvements have not gotten the job done.”[iii] In other words, we should heed the famous advice of Hippocrates: let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.

But, what food? “Today there are many loud and passionate voices in the health and diet scene dispensing so much information that it’s easy to get overwhelmed, confused and frustrated,” said Mark Sisson.[iv] Knowing how vital food is to human health, it’s time for physicians, the most trusted voices in the health field, to change their mindset and give credibility to the import of nutrition. “It’s time for doctors and hospitals to make the transition from being bystanders in food-related illnesses to becoming role-models and leaders in the fight for health,” says Dr. Barnard.[v] This must start with a change in the classroom.

MEDICAL EDUCATION

“I can’t believe what I’m not going to tell them,”[vi] Dr. Joel Kahn thought to himself, facing a room of 250 medical students in a preventative cardiology lecture. While acknowledging that it was a step forward to include such a course offering in medical school, Dr. Kahn knew the 50 minutes he was slotted to teach nutrition was mere window dressing.

Recent studies have found that medical schools offer, on average, 19 hours of nutrition education to medical students, mostly integrated into other course offerings, rather than as stand-alone nutrition education.[vii] As noted in the Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 80% of the nutrition instruction in medical schools is not specifically referenced to in the curriculum. Rather, “Nutrition instruction provided outside of designated courses could be considered diluted in importance – presented as an aside, instead of being given the emphasis it deserves as a core component of modern medical practice.”[viii]

To put this 19 hours of nutrition education into perspective, to become a registered dietitian in California, students must obtain at least a bachelor’s degree in the field, after which they must take part in a residency-like work program of at least 1,200 hours – overseen by a registered dietitian – before candidates may sit for the State licensing exam. In other words, many are receiving an extensive nutrition and dietary education – including 75,000 nutritionists and dieticians throughout the U.S. – but physicians are not among them.

In 1985, the National Research Council Committee on Nutrition in Medical Education recommended that medical students should enroll in a minimum of 25 to 30 classroom hours dedicated to nutrition. In 1989, The American Society of Clinical Nutrition recommended that 37 to 44 hours be dedicated to nutrition instruction during medical school. Though each recommendation is underwhelming, schools have nevertheless failed to meet this low bar.

“We’re not taught about the power of food in medical school,” said Dr. Michelle McMahon, a professor at NYU Medical School. “No one is taught that the changes that we make with our diet are probably the single most powerful thing we can do to determine our destiny.”[ix]

While the scientific community has not yet reached a consensus as to what constitutes the best human diet, it would nevertheless be a big step in the right direction for physicians to dedicate time to nutrition education, adding important voices to the discussion, and re-setting the current healthcare paradigm.

CURRENT DIETARY PARADIGM

As Dr. Cate Shanahan says in Deep Nutrition, “Ask ten people what the healthiest diet in the world is and you’ll get ten different answers.”[x] While there are hundreds of fad diets that have captured the public’s attention over the years, the broader, macro debate for dietary prominence over the last half century has been a battle between a plant-based diet and animal-based diet.

Dr. Michael Greger, a prominent figure in the documentary What the Health?, in his provocatively titled book How Not to Die, concluded that the “one unifying diet found to best prevent and treat many of these chronic diseases is a whole-food, plant-based diet, defined as an eating pattern that encourages the consumption of unrefined plant foods and discourages meats, dairy products, eggs, and processed foods.”[xi]

Dr. Dean Ornish, considered the father of lifestyle medicine, has written several books advocating a low-fat, plant-based diet, arguing such a lifestyle change not only stops the progression of heart disease, but reverses it. Similarly, Dr. Joel Kahn, in The Whole Heart Solution, said he was “convinced that the best diet for optimal heart health is a low-fat, plant-based, vegan diet…“[xii]

None of this comes as a surprise, right? After all, “Since the late 1970s, healthy eating has been defined to mean eating mostly plants: fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes, with minimal animal fats and red or processed meats,” said award-winning science journalist Gary Taubes. [xiii] This pro plant paradigm has its foundation built on the concept that saturated fat and high cholesterol cause cardiovascular disease. However, as Taubes argues, “No meaningful experimental evidence – no clinical trials – exists to support the contention that we would live longer, healthier lives by eating mostly plants rather than animal-sourced foods.” [xiv]

Despite that lack of evidence, this paradigm has nevertheless served as the foundation for the minimalist nutrition education received by our treating physicians. “When I was fresh out of medical school, if you had asked me what causes heart disease, I would have answered, ‘Fat and cholesterol, of course,’” said Dr. Shanahan. “I felt confident in this advice not only because it was what I had been taught, but because it seemed to make intuitive sense; I could picture fat accumulating inside a person’s artery, gradually choking it closed like cooking grease in a pipe.”[xv] Beyond medical school, the cholesterol theory of heart disease was endorsed by powerful and influential medical organizations - the American Medical Association, the American Heart Association, the American Diabetes Association, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Cardiologists – further cementing the theory in the minds of physicians.

HOW WE GOT HERE

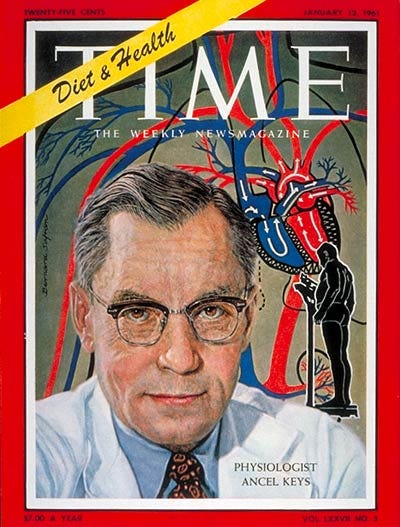

Americans found themselves to be in the midst of an unprecedented surge in heart attacks in the 1950s, with deaths caused by heart disease sharply on the rise. Ancel Keys, a biologist at the University of Minnesota, was commissioned to research the cause of this scourge. Keys, after a questionable study (using margarine made of partially hydrogenated vegetable oil – trans fats – rather than natural fat products) finding slightly lower levels of cholesterol in patients consuming less dietary fat, determined that high fat intake led to high cholesterol, causing heart disease. In the end, Keys ultimately settled on saturated fat as the true villain.[xvi]

Keys’s hypothesis made national headlines in 1957 after President Eisenhower suffered a heart attack. The President’s personal physician, Dr. Paul White – a cardiologist, renowned Harvard professor, and founding member of the American Heart Association (AHA) – was an ally to Keys. Following the President’s heart attack, in the press conferences and interviews that followed, White trumpeted Keys’s position on dietary fat.[xvii]

The AHA was a small, fledgling organization in 1948, when Proctor & Gamble funneled $1.74 million to truly launch the group, opening up seven chapters over the following year. As of 1960, the group had over 300 chapters and brought in over $30 million annually, arguably beholden to no one buts its sponsors. By 1961, Keys, now on the AHA’s nutrition committee, convinced the association to formally adopt the idea that Americans could reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke by cutting saturated fat and cholesterol from their diets. That same year, Keys hit the cover of Time Magazine and was dubbed “Mr. Cholesterol.”[xviii]

Now that saturated fat was to be avoided, unsaturated fats – primarily industrial seed (“vegetable”) oils – were pushed as the healthy alternative. These oils (canola, safflower, sunflower, corn, cottonseed, grapeseed, and soy) became popular as cooking oils after an endorsement from the AHA in 1961. In oil form, these products were less useful to the food industry, but hydrogenated oils – starting with Crisco and margarine – in solid form, transformed the food industry. These products, too, were endorsed by the AHA as part of a “prudent diet,” for those looking to avoid saturated fats. By the late 1980s, these hardened oils were used in most cookies, chips, baked goods, as well as fried and frozen goods. “They became the backbone of Big Food,” noted Nina Teicholz in Big Fat Surprise.[xix] This backbone, however, became the next villain.

A Dutch scientist, Martijn Katan, began studying, and giving voice to, the concerning effects of the consumption of hydrogenated oils, a voice that was amplified by Harvard epidemiologist, Walter Willett. By 2006 the negative effects (primarily, raising cholesterol) of these hydrogenated oils – also known as trans fats – whether partially hydrogenated or otherwise, were questioned to the point where the FDA required a separate line on all nutrition facts labels to identify the trans fat content. This was the beginning of the end of trans fats, which were formally banned by the FDA in 2015, and permanently out of the food supply as of January 2020.

With trans fats out of the picture, saturated fat and cholesterol are now front and center, once again, as the proverbial “face” of heart disease.

DID WE GET IT WRONG ON CHOLESTEROL?

“We still talk about cholesterol as ‘clogging up the arteries,’ like hot grease down a cold drain-pipe,” says Teicholz. “This vivid and seemingly intuitive idea has stayed with us, even as the science has shown this characterization to be a highly simplistic and even inaccurate picture of the problem.”[xx]

Coinciding with the FDA’s 2015 ban of trans fats was a determination by the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisary Committee – the group tasked with submitting formal scientific guidance to the USDA for its Dietary Guidelines – that “cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.” The committee found that available evidence “shows no appreciable relationship between the consumption of dietary cholesterol and serum [blood] cholesterol.”[xxi]

With the way cholesterol has been demonized over the last 60 years, most Americans are completely unaware of its vital importance to every cell in our body. “Cholesterol is a chemical we can’t live without,” explains Dr. Shanahan. It strengthens cell walls, controls what goes in and out of cells, can be turned into hormones, can communicate with DNA, and is required to help break down food. In other words, without cholesterol, we can’t grow, repair injuries, digest, reproduce and fight off infections, among other things. Cholesterol is found at its highest concentration in the brain.[xxii]

This concept that cholesterol is both good and necessary for the body is news to most:

“Like so much of the advice that we’ve received on heart disease prevention, the rationale for these changes remains more political and financial than scientific: LDL-cholesterol has a following and a long history; doctors everywhere understand it; the government has an entire bureaucracy, the National Cholesterol Education Program, committed to lowering it; academics have invested their careers in it; pharmaceutical companies, with their profitable LDL-cholesterol-lowering drugs, have promoted it. And LDL-cholesterol has long been the biomarker most widely used to condemn saturated fat, which, in a community of diet and disease researchers biased against that fat, made it especially appealing.”[xxiii]

LDL and HDL, often called the “bad” and “good” cholesterol, respectively, are not cholesterol at all. These lipoproteins are simply vehicles that distribute fat and cholesterol throughout the body. The liver produces the cholesterol needed by the body, while ramping up (or down) its production, as necessary. Ultimately, the “good” and “bad” claim is irrelevant – all cholesterol is good in the setting of a good diet, eating the right fats. Eating the wrong fats causes excessive LDL oxidation.[xxiv] According to Dr. Shanahan, “the oxidized fat and cholesterol have toxic effects on [LDL cells]” and “if your LDL continues to oxidize and your arteries are continually exposed to more and more toxic, oxidized fats and cholesterol, the wound, called a ‘fatty streak,’ never heals and the lesion continues to grow,” becoming plaque.[xxv]

In one of the primary studies relied upon by the medical community supporting the position that increased cholesterol levels increase the likelihood of death[xxvi], it was found (over 7.4 years) that the mortality rate (due to coronary heart disease) for those with a total cholesterol (TC) level of greater than 290 was 1.3%, compared to 0.3% for those with a TC level of 150. In this study of over 3,800 middle-aged asymptomatic men with hypercholesterolemia, this 1% differential was statistically manipulated to represent a 400%+ improvement in the treatment group by using a statistical method called relative risk reduction (RRR). Here, again, the placebo group had a mortality rate of 1.3% and the treatment group a rate of 0.3%. The math? 1.3/0.3 = 4.33 (or 433%).

Among the primary studies justifying the use of cholesterol-reducing treatment was a 7+ year study funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), which found that the treatment group (cholestyramine) had a 24% reduction in its mortality rate due to coronary heart disease.[xxvii] What did the data show? The mortality rate for those in the treatment group was 1.6%, while that in the placebo group was 2.0%, or a 0.4% difference between the two cohorts. With the use of RRR, that 0.4% differential was turned into a 24% differential by dividing 0.4 by 1.6. The outcome was touted as “a turning point in cholesterol-heart disease research,” by the director of the study.[xxviii] Dr. Thomas Chalmers, former President of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, described the interpretation of the results as an “unconscionable exaggeration of the data.”[xxix]

Many studies, over decades, have failed to reveal any evidence that higher cholesterol levels (or that cholesterol-reducing medication) materially impact all cause survival. For example, Scientific Reports published the results of a study of 12.8 million adults, finding the lowest mortality in those with cholesterol levels between 210 and 249, while noting that “total cholesterol levels <200 mg/dL may not necessarily be a sign of good health.”[xxx]

The Lancet – arguably the most respected medical journal in the world - published a study in 2001 following 3,572 men over 20 years, finding that the “data accord with previous findings of increased mortality in elderly people with low serum cholesterol, and show that long-term persistence of low cholesterol concentration actually increases risk of death.”[xxxi]

The BMJ published a meta-analysis of studies investigating LDL as a risk factor for all-cause mortality and/or cardiovascular disease mortality in individual 60 years of age or older. The study found that high LDL is inversely associated with mortality in most people over 60 years, a finding that is inconsistent with the cholesterol hypothesis (i.e., that cholesterol, particularly LDL-C, is inherently atherogenic, or a cause of the formation of fatty plaque in arteries). As the study went on to find that elderly people with high LDL live as long or longer than those with low LDL, the authors ultimately determined that the study “provides the rationale for a re-evaluation of guidelines recommending pharmacological reduction of LDL-C in the elderly as a component of cardiovascular disease prevention strategies.”[xxxii]

Considering the vital importance of cholesterol to our overall health – and the fact that the liver produces the vast majority of the cholesterol circulating throughout the body – it appears nonsensical to conclude that a slight variation in serum cholesterol levels (whether up, from cholesterol-rich food, or down, from statins or other cholesterol-reducing medication) would have a material impact on mortality. The evidence that has demonized cholesterol over the years appears – at least arguably – to be anywhere from fraudulent, at worst, to flimsy, at best, while there’s ample evidence to suggest that cholesterol is simply not a culprit in the fight against cardiovascular disease.

DID WE GET IT WRONG ON FATS?

“Eat Butter,” said the June 12, 2014 cover of Time Magazine. “Scientists labeled fat the enemy,” noted the sub-headline. “Why they were wrong.”[xxxiii] As argued by Dr. Robert Lustig in the Time article, “The argument against fat was totally and completely flawed.”

In 2010, the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition conducted a meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies, which showed that there is no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) or cardiovascular disease (CVD).[xxxiv]

In 2014, the Annals of Internal Medicine published a meta-analysis of nearly 80 trials – 27 of which were conducted by the “gold standard” (randomized, controlled trials) – concluding that “current evidence does not clearly support cardiovascular guidelines that encourage high consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids and low consumption of total saturated fats.”[xxxv] In other words, there’s no evidence to support the AHA and government’s decades-old recommendations to avoid saturated fats and replace them with unsaturated fats.

In 2017, The Lancet published findings from a study following the dietary intake of over 135,000 people in 18 countries (median follow up of 7 years). The researchers concluded that “high carbohydrate intake was associated with higher risk of mortality, whereas total fat and individual types of fat were related to lower total mortality.” Further, “Total fat and types of fat were not associated with cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, or cardiovascular disease mortality, whereas saturated fat had an inverse association with stroke.” In light of these findings, the authors recommended that “Global dietary guidelines should be reconsidered…”[xxxvi]

Global dietary guidelines, including the U.S. Dietary Guidelines – updated every five years since 1980 – have, for the most part, held firm in the position that saturated fat intake should be minimized. According to the American College of Nutrition, “It is now increasingly recognized that the low-fat campaign has been based on little scientific evidence and may have caused unintended consequences.”[xxxvii]

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES - UNSATURATED FAT (& LOW CHOLESTEROL) FALLOUT

Fat Fallout

It’s the push away from saturated fats and over to unsaturated fats that created a never seen before human diet, a “vast nutrition experiment,” according to Philip Handler, former President of the National Academy of Sciences.[xxxviii] “At the behest of government panels, nutrition scientists, and public health officials, we have dramatically changed the way we eat and the way we think about food, in what stands as the biggest experiment in applied nutritionism in history,” echoed Michael Pollan.[xxxix]

The term “nutritionism” was coined by professor Gyorgy Scrinis in his book of the same title, and later popularized by Michael Pollan in In Defense of Food. “Nutritionism – or nutritional reductionism – is characterized by a reductive focus on the nutrient composition of foods as the means for understanding their healthfulness, as well as by a reductive interpretation of the role of these nutrients in bodily health,” explains professor Scrinis.[xl] “Nutrition experts have, for example, made definitive statements about the role of single nutrients, such as the role of fat or fiber, in isolation from the foods in which we find them.” In other words, the experts have ignored the Aristotelian mantra, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

Until the turn of the 20th century, no one was talking about macro or micro-nutrients, nor was “nutritionism” a thing. Talking about food based on chemical components – protein, fat, carbs – gets us away from talking about the most important aspect of any food, its source,” says Dr. Shanahan.[xli]

Before Ancel Keys’s campagain, the average American ate far more saturated fat and cholesterol rich foods, with little to no history of heart attacks. In 1900, heart disease was rare, and by the middle of the century, heart problems were the #1 killer of men. Now? Heart disease is the #1 killer of both men and women. This nutrition experiment in which we’re all partaking involves a movement away from nature and towards labs and industrial manufacturing; away from whole foods towards processed foods; away from farm-to-table and towards factory-to-table. “It’s striking how quickly Americans have come to accept that it’s normal for almost everything we eat to come out of a plastic bag, carton, or cardboard box,” observed Kristin Lawless, in Formerly Known as Food.[xlii]

The era of nutritionally engineered foods has created what is essentially food science - the introduction of highly processed, low-fat, and vitamin “fortified” food products, many of which are labeled “heart healthy” or otherwise stamped with the approval of organizations such as the AHA. As Michael Pollan put it, “Nutritionism supplies the ultimate justification for processing food by implying that with a judicious application of food science, fake foods can be made even more nutritious than the real thing.”[xliii]

After consumers’ concern over whether they were, in fact, buying the ‘real thing’ in the early stages of the industrialization of food production, a regulatory pathway was put in place just in time for “big food” producers to deceive consumers. The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938 was passed in response to concerns over the adulteration of ordinary foods, including butter and olive oil. Any food product resembling standardized food, but not matching the expected standard was to be labeled “imitation.” Without any involvement from Congress, the FDA passed a regulation in 1973 that, in effect, amended this law, so as to “give manufacturers relief from the dilemma of either complying with an outdated standard or having to label their new products as ‘imitation’…[since] such products are not necessarily inferior to the traditional foods for which they may be substituted.”[xliv] This new policy allowed for imitation products – made with seed (vegetable) oils and other fillers – to avoid carrying the “imitation” label, so long as the products were properly “fortified” to add similar amounts of vitamins and minerals as the real thing; “nutritionism” at its finest, opening the floodgates for the production of countless unnatural food products.

The USDA’s 2020-2025 Guidelines suggest that “strategies to shift intake [of fatty acids] include cooking with vegetable oil in place of fats high in saturated fat, including butter,” while vegetable oils are mentioned as part of a healthy diet no less than 7 times in the Guidelines.[xlv] Similarly, Harvard’s School of Public Health, via its “Healthy Eating Plate” recommends Canola, Corn, Soy and Sunflower oils (“vegetable oils”) as a “healthy oils,” while the school’s “Nutrition Source” content labels vegetable oils “good” unsaturated fats.[xlvi] According to Dr. Cate Shanahan, “vegetable oil is undoubtedly the most unnatural product we eat in any significant amount,” yet it serves as the foundation for nearly all food products in the modern world.

Cholesterol Fallout

The so called “turning point” in the treatment of high cholesterol, as noted above, was the beginning of the statin era. The study that served as Lipitor’s shining moment, too, used RRR to turn a 1.1% reduction in heart attacks into a claimed 36% benefit.[xlvii] In fact, one of Lipitor’s early advertisements claimed that it “reduces risk of heart attack by 36%,” while an asterisk points us in the direction of truth: “that means in a large clinical study, 3% of patients taking a sugar pill or placebo had a heart attack compared to 2% of patients taking Lipitor.” The result? While under patent protection, Lipitor was the highest selling drug of all time. Now, almost 1 in 3 Americans take statins.

Dr. John Abramson of Harvard Medical School, led a 2013 review of a meta-analysis (of 27 clinical trials completed by 2009) previously conducted by the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration published in 2012.[xlviii] Dr. Abramson’s review of the data revealed that statin therapy prevents one serious cardiovascular even out of every 140 low risk patients (five year risk <10%) treated for five years, and does not at all reduce all cause mortality or serious illness, all while creating an 18% risk of side effects ranging from minor and reversible to serious and irreversible.[xlix]

With regard to side effects, studies have shown that statins cause increased risk of myopathy (muscle disease) and increased incidence of diabetes, with some evidence that the medication may also cause cognitive deficits.[l] In fact, recent studies have shown that for those with mild cognitive decline and low to moderate cholesterol levels, lipophilic statin (such as Lipitor and Zocor) use more than doubles the risk of converting to dementia.[li] Other studies have found that statins may actually cause, rather than prevent, atherosclerosis and heart failure.[lii]

Overall, the evidence does seem to show that statins may benefit about 1% of the population, though even for that minority, it remains a question as to whether the benefits outweigh the risks. As Dr. John Abramson once said, “Dying with corrected cholesterol is not a successful outcome.”[liii]

WE ARE WHAT WE EAT – SOURCING, CHEMICALS & ADDITIVES

“You are what you eat, it’s often said, and if this is true, then what we mostly are is corn – or, more precisely, processed corn.”[liv] Corn and other grains, usually highly processed, dominate the Western diet. Ultra-processed food accounts for 70% of food consumed in the U.S.[lv]

Whether or not part of the 70% - whether ultra-processed or not – all foods are subject to toxicity. Herbicides, otherwise known as weed killers, are used to kill off unwanted plants and leave only the wanted crop to survive. Of course, the herbicides may (and do) find their way onto/into fruits and vegetables we all consume. Processed foods generally contain preservatives, to maintain shelf-life, and other chemicals to affect taste and appearance.

“More than 10,000 chemicals are allowed to be added, directly or indirectly, to human food pursuant to the United States’ (US) Food Additives Amendment of 1958 as administered by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), found Thomas Neltner in Reproductive Toxicology.[lvi] These chemicals perform many roles - preserving flavor, enhancing taste or appearance, preserving spoilage, and as constituents of packaging – and are “allowed into our food as a ‘food additive’ or substance ‘generally recognized as safe,’ in either case which requires an affirmative determination that their use is safe, which is often determined by the manufacturer itself.” According to Neltner, “The large majority of these chemicals have not been sufficiently researched to reasonably determine a safe dose, while less than 38% of the chemicals are backed by animal feeding studies to evaluate their health effects.”[lvii]

Therefore, even if we were all in agreement as to exactly what constitutes the perfect human diet, and regardless of how healthy you think your food choices are, it’s been argued, “the saturation of our environment with industrial chemicals, along with the deterioration in the quality of even our most basic foods, represents the biggest health crisis facing us today.”[lviii]

In other words, our food’s food (or environment) is every bit as crucial to our health as the food itself. This is the case not only with respect to plant-based products and the chemicals used for their growth and preservation, but perhaps doubly-so for animal-based products as well. As compared to cattle served with industrial corn feed, grass fed beef has the benefit of having less fat, but more healthy fat overall, including omega-3 fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acids.[lix] All products coming from a cow – milk, yogurt, cheese, butter, and the beef itself – are clearly healthier when the cow is grass-fed, and even healthier when that grass is chemical-free.

MOVING FORWARD

As summarized in Big Fat Surprise, “The disturbing story of nutrition science over the course of the last half-century looks something like this: scientists responding to the skyrocketing number of heart disease cases, which had gone from a mere handful in 1900 to being the leading cause of death by 1950, hypothesized that dietary fat, especially of the saturated kind (due to its effect on cholesterol), was to blame. This hypothesis became accepted as truth before it was properly tested. The hypothesis became immortalized in the mammoth unproven dogma. And the normally self-correcting mechanism of science, which involves constantly challenging one’s own beliefs, was disabled. While good science should be ruled by skepticism and self-doubt, the field of nutrition has instead been shaped by passions verging on zealotry. And the whole system by which ideas are canonized as fact seems to have failed us.”[lx]

While systems have failed us, Dr. Nadir Ali, a cardiologist, believes the medical world has somewhat failed to live up to its calling. “We have abdicated our clinical responsibility to the key opinion leaders, Big Pharma, [the] food industry, and various medical societies like [the] AHA and American College of Cardiology, and relinquished our critical thinking abilities.”[lxi]

Lifestyle-related diseases, primarily related to diet, dominate the health landscape, yet physicians remain bystanders. While conflicts, bias, and self-interest will remain an issue in the study and sourcing of dietary recommendations moving forward, with greater involvement from the medical community, especially physicians, shining a light on both truths and mis-truths, we’ll all be better off.

[i] Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. [ii] Lustig, Robert. Metabolical: The Lure and the Lies of Processed Food, Nutrition, and Modern Medicine [iii]https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/physicians-role-nutrition-related-disorders-bystander-leader/2013-04[iv] Saladino, Paul. The Carnivore Code: Unlocking the Secrets to Optimal Health by Returning to Our Ancestral Diet [v] Ibid. [vi] Kahn, Joel. The Whole Heart Solution. [vii] Adams, Kelly M. Nutrition Education in U.S. Schools: Latest Update of a National Survey. Association of American Colleges [viii] Ibid. [ix] What the Health? Directed by Kip Andersen and Keegan Kuhn. 2017. [x] Shanahan, Catherine. Deep Nutrition: Why Your Genes Need Traditional Food. [xi] Greger, Michael. How Not to Die. [xii] Kahn, Joel. The Whole Heart Solution. [xiii] Taubes, Gary. “The Keto Way: What if Meat is Our Healthiest Diet?” Wall Street Journal, January, 2021 [xiv] Ibid. [xv] Shanahan, Catherine. Deep Nutrition [xvi] Teicholz, Nina. The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat, and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet. [xvii] Ibid. [xviii] Ibid. [xix] Ibid. [xx] Ibid. [xxi] https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf [xxii] https://drcate.com/cholesterol-what-the-american-heart-association-is-hiding-from-you-part-1/ [xxiii] Teicholz, Nina. Big Fat Surprise. [xxiv] https://drcate.com/cholesterol-what-the-american-heart-association-is-hiding-from-you-part-1/ [xxv] Ibid. [xxvi] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3773199/ [xxvii] https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/391065 [xxviii] http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,921647,00.html [xxix] Taubes, Gary. Good Calories, Bad Calories: Fats, Carbs, and the Controversial Science of Diet and Health. [xxx] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-38461-y [xxxi] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(01)05553-2/fulltext [xxxii] Ravnskov U, Diamond David. Lack of an association or an inverse association between low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010401. Doi: 10/1136/bmjopen-2015-010401 - https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/6/e010401 [xxxiii] https://time.com/magazine/us/2863200/june-23rd-2014-vol-183-no-24-u-s/ [xxxiv] The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Patti W. Siri-Tarano, Vo. 91, Issue 3, March 2010 https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/91/3/535/4597110 [xxxv] https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M13-1788?articleid=1846638& [xxxvi] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28864332/ [xxxvii] Hu, Frank B. Journal of the Amer. College of Nutrition, Vol. 20, 1, 5-19 (2001). [xxxviii] Insert [xxxix] Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food. [xl] Scrinis, Gyorgy. Nutritionism. [xli] Shanahan, Catherine. Deep Nutrition. [xlii] Lawless, Kristin. Formerly Known as Food: How the Industrial Food System is Changing Our Minds, Bodies, and Culture [xliii] Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food. [xliv] Proposed Rules. Federal Register. November 27, 1991, 56(229). [xlv]https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/resources/2020-2025-dietary-guidelines-online-materials[xlvi] https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/ [xlvii] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12686036/ [xlviii] https://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6123 [xlix] https://www.bmj.com/content/347/bmj.f6123 [l] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6019636/ [li] https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/62/supplement_1/102 [lii] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/17512433.2015.1011125 [liii] https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/wonder-drugs-that-can-kill [liv] Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. Pollan, Michael. Penguin Books, 2006. [lv] Lustig, Robert. Metabolical. [lvi] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890623813003298 [lvii] Lawless, Kristin. Formerly Known as Food. [lviii] Ibid. [lix] Robinson, Jo. Pasture Perfect: How you can benefit from Choosing Meat, Eggs, and Dairy Products from Grass-Fed Animals. [lx] Teicholz, Nina. Big Fat Surprise. [lxi]